The Software That Listens to Trees (And Taught Me I Was Building It for the Wrong Reason)

When producer Ishq first mentioned to me how cool it would be to build software that could turn trees into music, I thought I had it figured out. Point a camera at a swaying tree, extract the movement data, map it to MIDI notes. Nature becomes soundtrack. Easy.

Six months into the project, watching my software track an oak in nearby field on a breezy afternoon, I finally understood what I'd actually built. MIDI For Trees wasn't really for trees at all; it was for anyone who'd ever wanted to collaborate with something completely outside their control. Something ancient, patient, and utterly indifferent to human timing.

The tree doesn't care about your chord progressions. It moves when the wind moves it. And that's exactly the point.

How Do You Teach Software to Watch a Tree?

The technical challenge seemed straightforward: track movement, generate music. But trees aren't dancers. They don't have joints or limbs in the traditional sense. A tree is thousands of independent moving parts; branches, clusters of leaves, entire sections of canopy all responding to the same wind in slightly different ways.

My solution was to teach the software to see colour and movement at multiple scales simultaneously.

First, you tell the system what to look for: the specific greens of leaves in sunlight, the browns of dead leaves, the darker tones of shadows in the canopy. (Technically, these are HSV colour values - hue, saturation, and brightness - but what matters is that you're teaching it to recognize "this is tree" versus "this is sky.")

Then comes the clever bit: scale detection. The software looks for these colours in regions ranging from tiny (individual leaf clusters) to massive (an entire tree crown). This means it can track the flutter of small leaves and the slow sway of thick branches at the same time.

Between each video frame, the software calculates how each coloured region has moved. A gust hits the upper canopy? It sees dozens of small movements propagating downward. A steady breeze? It tracks the whole tree leaning and swaying as one organism.

From Vision to Voice

Here's where movement becomes music.

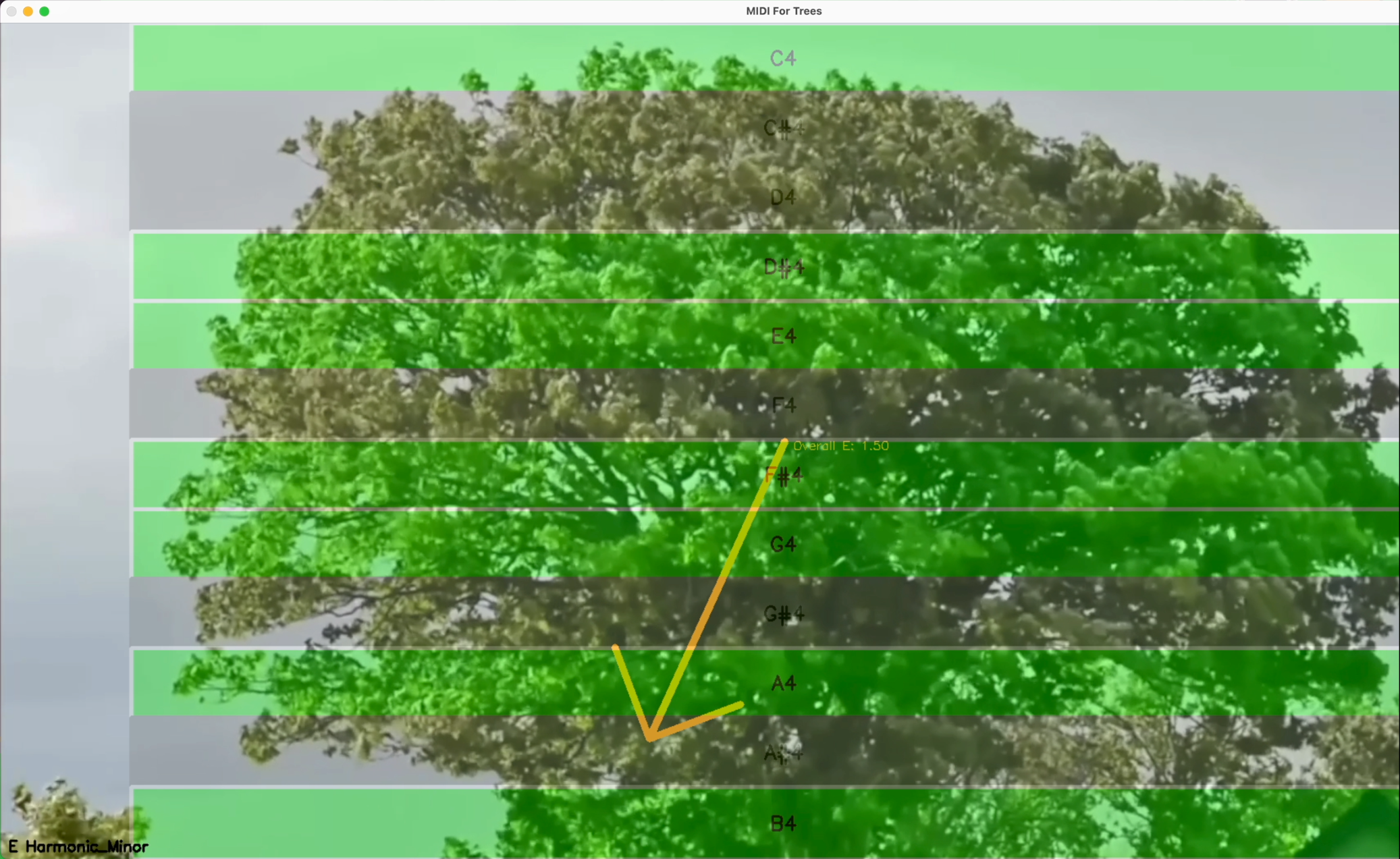

All those individual movements, every swaying branch, every cluster of leaves catching wind, get averaged into what I call the Overall Movement Vector. Imagine a large orange arrow in the centre of your video frame, constantly shifting direction and length as it follows the tree's motion.

Now picture a piano keyboard laid over your video. As that arrow moves, it passes through different notes. Touch a key zone, trigger that note. The tree's sway becomes a melody.

The orange Overall Movement Vector arrow.

But a tree isn't just one thing moving. It's a thousand small movements happening in chorus. So the software also tracks individual movement vectors, one for each detected region of colour. These trigger a second layer of notes laid out in a grid across the frame. Small leaves flickering in the upper canopy might trigger high, quick notes. Thick branches swaying below might hit deeper, sustained tones.

The tree is essentially playing itself, on two instruments at once.

The Invisible Orchestra: Expression Data

Notes alone don't make music; you need dynamics, feeling, expression. This is where MIDI For Trees goes from an "interesting experiment" to something that actually sounds alive.

The software outputs continuous streams of control data based on what the tree is doing:

Direction, strength, and energy of the overall movement; is the tree leaning hard into a gust, or gently rocking in calm air?

Movement density; how many regions are active in each part of the frame? A tree full of small, fluttering leaves creates a different texture than a tree with fewer, larger branches.

Energy distribution; the software calculates a "centre of mass" for all the detected movement, tracking where the tree's energy is concentrated at any moment.

Average energy across all vectors; is this a quiet moment or is the whole tree thrashing?

Every one of these data streams can be mapped to musical parameters: volume, filter cutoff, reverb depth, note velocity. The result is music that doesn't just respond to the tree's movement - it embodies it.

What I Got Wrong (And Right)

When I started building MIDI For Trees, I imagined I was creating a tool for trees. A way to give them a voice or translate their language - all those well-meaning but slightly patronising ideas we have about nature.

What I actually built was a tool for listening.

The tree doesn't need software to have a voice. It's already moving, already responding to its environment with perfect sensitivity. What the software does is slow me down enough to notice. It makes me wait for the wind. It makes me pay attention to the difference between an oak's heavy sway and a birch's shimmering flutter.

The music that emerges isn't from the tree, exactly. It's from the collaboration; the tree's movement filtered through choices I've made about scales, note mappings, which data streams to emphasise. The tree provides the timing, the rhythm, the unpredictability. I provide the palette.

And that's what makes it work. Neither of us is in control. Neither of us could make this music alone.

It Was Never Really About Trees

Here's the secret I stumbled into: MIDI For Trees isn't actually tree-specific at all.

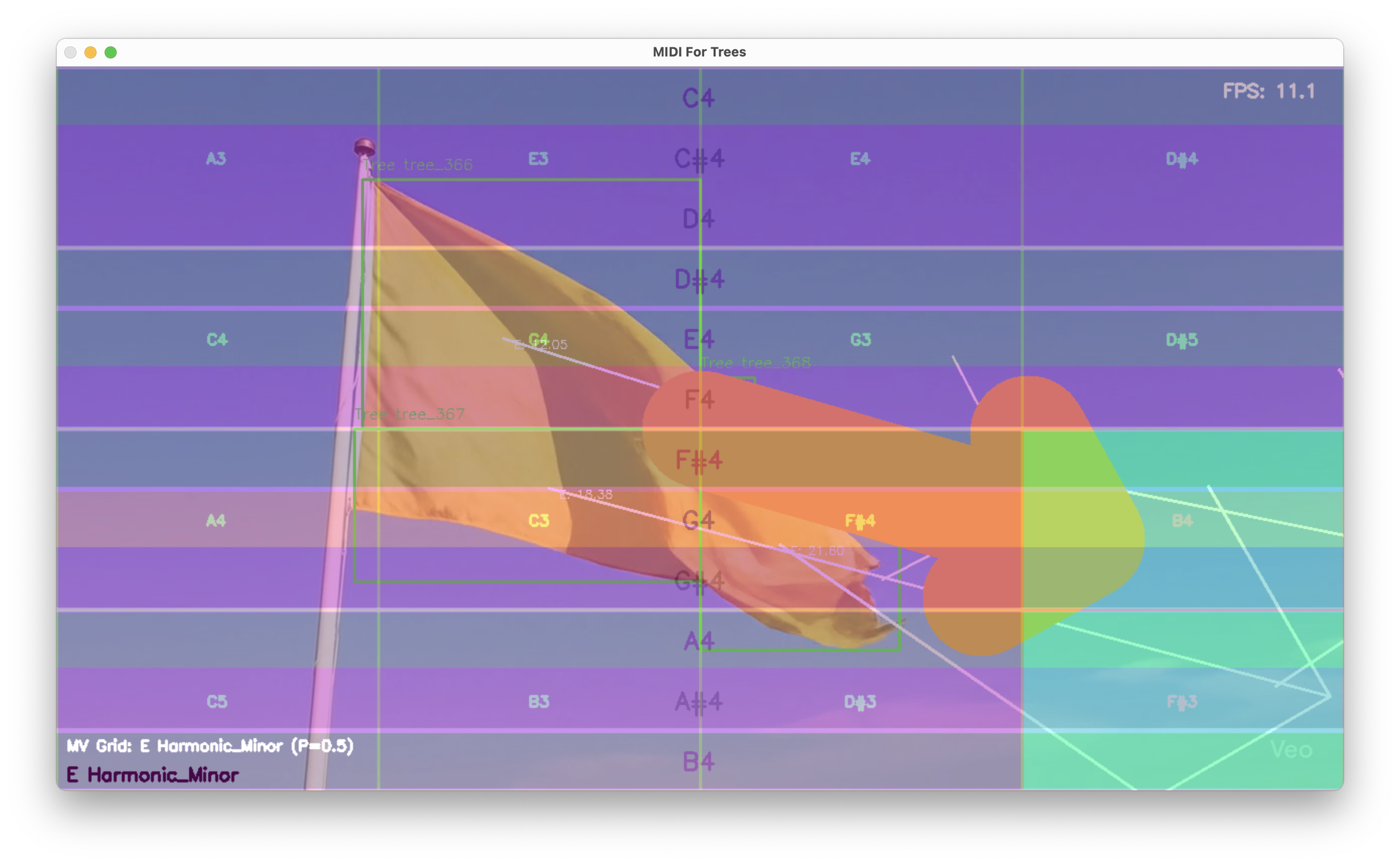

At its core, the software tracks the movement of colour. Any colour. The "trees" part is just where I started because that's what Ishq and I were talking about that day. But the system doesn't know it's looking at leaves. It just knows: "Track these greens as they move through the frame. Track these browns. Calculate their motion."

Which means you could point it at storm clouds; those rolling greys and whites churning across the sky. The software would lock onto them, track their drift and billow, and generate music from their slow, inevitable march across your view.

Or aim it at a rainbow flag snapping in the wind. All those stripes of colour, each one rippling at slightly different frequencies, catching gusts at different moments. The software would track each band independently; red flickering up top, violet undulating below, and you'd get this layered, polyrhythmic composition from a simple piece of fabric.

Who needs trees when you have flags!

A lava lamp. Traffic lights changing in sequence. Autumn leaves tumbling past a window. Paint mixing in water. Anything with colour that moves.

The moment I realised this, the name "MIDI For Trees" suddenly felt both perfectly right and completely wrong. Right, because trees are what taught me to see the potential. Wrong, because I'd accidentally built something far more universal than I'd intended.

I'd built a system for making music with anything that won't sit still.

Where It Goes from Here

MIDI For Trees is still evolving. The core engine I've described here is just the foundation. There are additional layers for allowing many MIDI instruments to be directed, modules for splitting up the Overall Movement Vector across several regions.

But the fundamental idea remains: point it at something that moves on its own terms, step back, and listen to what emerges.

If you want to try it yourself, come join the Ljomi Lounge Discord server. And if you're curious about the technical implementation, the actual code, the computer vision techniques, the MIDI routing architecture, just ask!

For now, I'm going to go sit in my back garden and watch the trees; the wind's picking up.

Special thanks to Ishq for the original conversation that sparked this project.